It seems more often than not, we celebrate the artist, but rarely the muse. Sure the muse is mentioned (Picasso’s Dora Maar, Man Ray’s Lee Mitter, Banksy’s Kate Moss) but they’re usually cited as inspirations for the artist, a part of the artistic process, an object to be transformed and reinterpreted. But what about the muses themselves? Is it possible to get a life after being a muse? Is it possible to create for oneself and not end up feeling bitter, used up, and locked in the past?

The answer to these questions can be found with the muses themselves, some of them dead and forgotten, some of them living exceptional narratives – how they handled the sudden notoriety, how they handled the delirium of identity, and how they handled the transition once the eye of the beholder became the eye of the beheld.

George Dyer – the self-destruction

George Dyer was the dark and tumultuous lover/muse of the painter Francis Bacon, who entered Bacon’s life when he was caught by Bacon burgling the artist’s home. In Dyer, a brawny man of thirty, who’d lived a desultory life fitted with delinquency and drink, Bacon found a kindred tortured soul and took to him immediately. During their passionate years, Bacon’s work focused obsessively on Dyer as the subject. Bacon describes « Dyers perception » of the artist’s works as giving meaning to « the brief interlude between life and death. »

Bacon’s artistic and personal infatuation with his muse eventually infused Dyer with an equally frenzied obsession with his own role in the process – that as revered creative source, which ultimately proved lethal for Dyer. Devastated by Bacon’s waning interest in him and feeling rejected by the artistic community, and also in the throes of severe alcoholism, Dyer ended his life two days before Bacon’s 1971 retrospective at the Grand Palais in Paris.

Perhaps one could look at Dyer’s suicide as the ultimate revenge, a way of stealing the only life blood (not to mention publicity) of Bacon’s work while at the same time, appropriating the work, he felt he helped Bacon create, for himself.

Amanda Lepore – Evolution and Transformation

The muse that probably bests exudes the idea of evolution and transformation is Amanda Lepore, muse to David LaChapelle and Terry Richardson. A recording artist, model, and transgender public figure, Lepore underwent gender reassignment surgery at the age of seventeen.

Transforming from male to female, suburban housewife to NYC dominatrix, muse to icon, performance artist to public figure, Lepore’s trajectory is the very embodiment of physical, creative, and personal evolution, taking control of her own body, her own role as muse as well as her own career.

One could say that Lepore’s form of muse is almost that of a benevolent benefactor, patron of the arts, civil servant, and cultural hero, seeking revenge only in the form of socio-cultural change and progress. White Dyer’s death was a high-wattage statement, Lepore generated the same electrifying voltage by living – blazing traits and detonating both the art world and the dominating world views by giving and taking as she pleased.

Edwige Belmore – Muse of the times

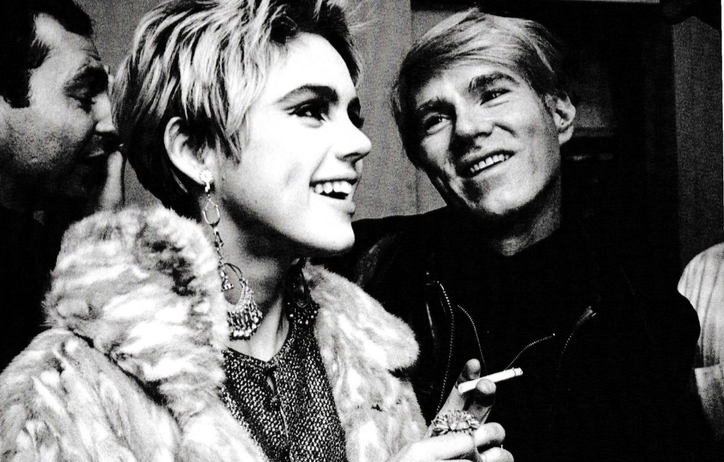

Edwige Belmore, the former muse for several renowned photographers: Helmut Newton, Pierre and Gilles, Jean Baptiste Mondino, and Andy Warhol could be considered a symbol for an entire cultural movement. Discovered at 19 by Fabrice Emaer, the owner and creator of the Palace (Paris’s studio 54), Edwige ruled the velvet rope, and in the process, Paris night life.

It didn’t matter who you were, what connections you had, Belmore only permitted people she thought were extravagant enough or possessed a certain it quality to enter. During that time, she became a muse for Newton and company, while also appearing on the runway for Jean Paul Gautier and Thierry Mugler.

« Seventy or eighty of them really wanted to take my picture and each one is very different, because it’s their interpretation of that muse. I think it’s something they saw in me, because I felt comfortable in every single photo, » recalls Edwige.

In the early 80’s, Edwige relocated to NYC. Attracted by the infinite possibilities offered by the NYC underground nightlife, Belmore initiated numerous parties and established recurring nighttime festivities, while even having an affair with a young Iggy Pop, which started in an elevator. Unlike many of her nightlife contemporaries, Belmore managed to transition into daytime, becoming a set designer for MTV, an art director for The Standard Hotel in NYC, and now a maitresse de maison at the Agnes b store in Soho.

For Belmore, muses must be adjustable – inherently malleable, but forever themselves. As Edwige puts it, a muse is merely « Someone that inspires you, so it doesn’t really matter what she looks like. It could be a frog. » But the question poses itself: Does a muse ever get to see themselves through their own eyes?

» Through my life I thought yeah, I’m great. Everybody is taking my picture. I’m in books, in magazines. l’m singing. I’m on stage. I’m travelling. I still took it as life gave it. I didn’t have a mission. I took it as a journey. I kept going, and it’s not just low self-esteem, it’s also that… I never assumed the cloak of an artist, I never finished anything: I started books I never finished, so I never was a writer. I started a singing career but I never finished so I’m not really a singer. I definitely did not want to be a model, I was just, again, a muse, and even philosophidy, I just keep on going. I don’t know if I’m actually inspiring anyone nowadays, I know I did inspire photographers, but with regular people, it’s a different thing. »

Drawing from her past roles instead of refuting them, Edwige has created a life of creating for herself, managing to harness the traits and the forces that made her a muse and putting them into use for her own endeavors.

At Agnes b, she’s made people feel at home, a quality that seems inherent in her personality. « l’m definitely good at cheering people up and making them feel welcome, which is really nice when you walk into an impressive place. I know that when I walk into a store I’m already holding my breath because everyone there is so corporate and stiff, they’re like robots. You see the way I look and dress, I am extremely diplomatic, and good with social environments. »

A muse can be defined in terms of how she inspires others, but what inspires a muse? And what form does that inspiration take when it is not co-opted by another?

« For me the whole concept of inspiration is keep your eyes open and it’s not a matter of making fun, it’s a matter of feeling and absorbing the whole world around you. »

Even though Edwige never considered herself an artist, she started taking photographs and was featured in a group show earlier in September, focusing on the seven deadly sins. She also joined forces with a close friend to launch a jewelry line composed of feather necklaces. « Those feathers are magical. It’s not just a feather; it looks like a weapon, a blade, an armor. Using something so organic and fragile and put a whole armor on it, » which basically describes herself and the concept of the muse.

To Belmore, perhaps the muse is both a source and an artifact – a rough outline of someone we don’t need to know, we just observe.

« l was thinking about it on my way here, » says Edwige, « the only person in the world I could actually relate to who I am today is Nico. People sing her songs and try to look like her … and at the same time she wasn’t that famous – yet she was icon. An Iconic figure. And I feel very much in that category. »

When asked about the modernization and mutation of the muse, Edwige sees Kate Moss as the definition of a contemporary culture muse, « because of her attitude and her disrespect: being busted for cocaine and yet getting the Chanel campaign a week later shows different values. »

Asked on whether her perception of being a muse has changed with time, Edwige is very clear.

« When I was the queen of punk, I was like, no futur, meaning, I’m going to die pretty soon. When I turned I was like, no future (I don’t know what l’m gonna’ do later and then later, today, at 50 something, I’m like, yup, you were right, no future. I believe in a journey longer than this earthly one. No future, because there is no end, it’s like a cycle. Never starts, never ends. »

And yet the muse is there, always, found then lost then found again, even after the music has stopped.

By Alice Carriere and Adele Jancovici